What is Dynamic Range in Audio? How Loudness, Compression, and Limiting Affect Your Mix

Dynamic range is one of the fundamental principles of audio that we need to understand if we are to create the best possible mixes.

In this article, we explain what dynamic range is and why it’s important, we then delve into some of the practicalities of this subject – explaining why an understanding of this topic will help you to craft better mixes and masters.

What Is Dynamic Range in Audio?

In a nutshell, dynamic range is the difference in decibels (dB) between the quietest and the loudest sounds in a mix or audio file. A track can be described as having a large dynamic range if there is a big difference in level between its loudest and quietest moments.

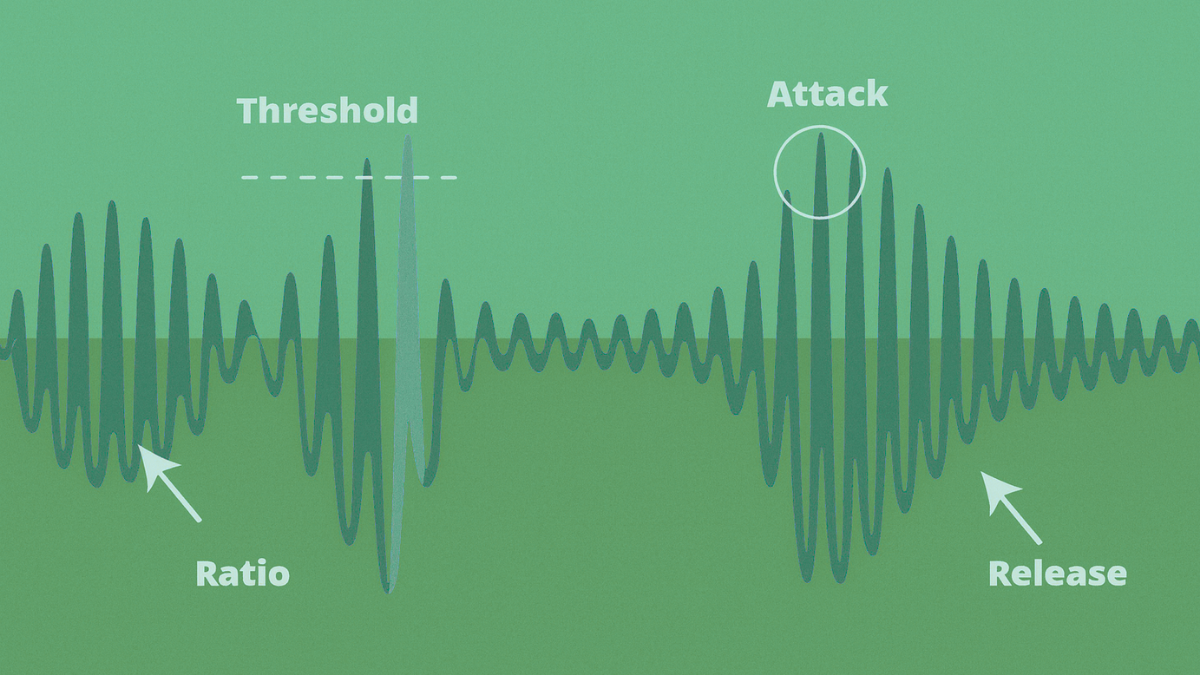

We can use tools such as compressors and limiters to make the dynamic range of a mix smaller; this is done by bringing the levels of the loudest and quietest parts of the mix closer together.

Audio playback systems also have a dynamic range. This is the difference between the quietest and loudest sounds that they can faithfully reproduce. The bottom end of this range is called the noise floor.

When the level of playback drops below the noise floor, you won’t be able tell the difference between the audio you are auditioning and the system noise of the playback equipment. The upper end of a playback system’s dynamic range is the point at which it starts distorting.

Why Is Dynamic Range Important in Music?

Dynamic range has always been important in music. Contrast is vital for creating moments of impact and drama. If the verse of your song is already at maximum volume then what do you do when you get to the chorus? There’s nowhere left to go.

Changes in dynamics are often very obvious in orchestral music and jazz, but even in modern, ultra-compressed genres such as EDM, breakdown sections are incredibly important. The drops sound powerful because they are heard in comparison with these quieter sections.

Dynamic range is also important when we mix and master our music. If a master has a large dynamic range, you will hear sounds with large attack transients much more clearly as they will really punch through the mix. As we compress a mix or master more, the dynamic range shrinks and these loud transients don’t pop as far out of the mix, meaning that detail can be lost.

How Much Dynamic Range Can We Hear?

The maximum dynamic range we can experience is limited to a range that starts at 0dB (silence) and goes up to 120-130dB, at which point the sound becomes so loud that it is painful.

Most modern music will not ping-pong back and forth between these extremes. Compressors and limiters are often used to shrink the dynamic range of musical performances in order to make them more consistent in level.

What's The Difference Between Dynamic Range and SNR?

SNR stands for signal-to-noise ratio, and although this concept is related to dynamic range, it is not the same thing. When recording audio it is important to ensure that your input signal is sufficiently loud that any system noise produced by your recording equipment is mostly drowned out.

If you record without enough gain on your input channel, this will result in a poor signal to noise ratio; there will be obvious hum or hiss present in your recording.

A good signal-to-noise ratio results from ensuring that the average level of a signal is as far as possible above the noise floor of your recording equipment, without being so high as to risk distortion. It is, therefore important to consider dynamic range when setting your input levels.

Dynamic Range and Musical Genres

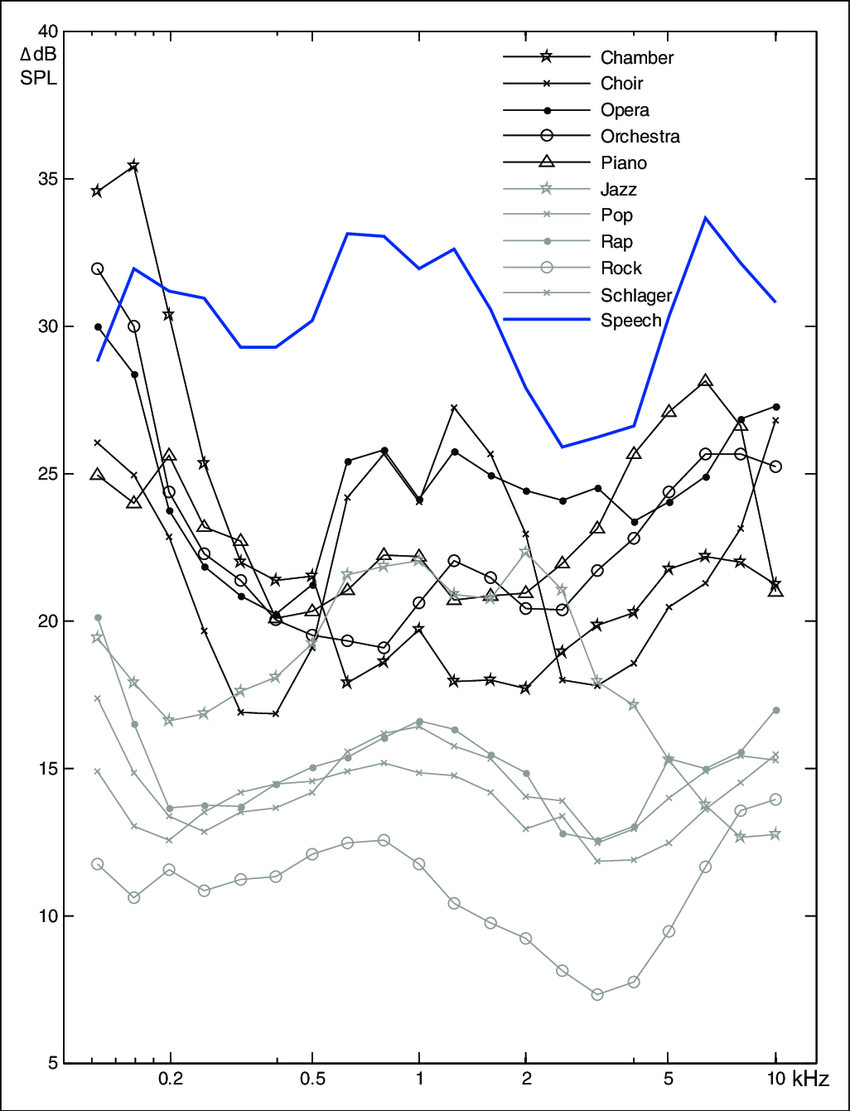

We’ve already alluded to it, but it’s worth pointing out that dynamic range can vary enormously from genre to genre. This study shows that modern genres such as rock, pop and rap have a much smaller dynamic range than classical genres such as chamber, opera, orchestral and piano music. The dynamic range of Jazz falls somewhere in between the modern and the classical genres.

Dynamic range comparison between different music genres and speech across frequency. The dynamics are calculated as the difference between the 99th and 30th percentiles according to the IEC 60118-15 standard. SPL ¼ sound pressure level.

This is primarily because modern genres make much greater use of dynamic range compression (normally just known as compression) during the mixing and mastering process. The subject of compression is worth looking at in-depth, but to summarise briefly, a compressor works by attenuating the loudest peaks in a recording.

Often the entire signal is then boosted, meaning that we end up with a louder signal, but also one that has a smaller dynamic range than the original recording. In modern genres it is common to individually compress many of the component parts of a mix, before then compressing the master channel.

By way of contrast, any compression on a classical performance would likely only be on the master channel, and if used it would normally be much more subtle than that you would generally hear on a rap, pop or rock recording.

This is all worth considering when working on your own recordings – what genre are you working in? Are you using a genre-appropriate amount of compression?

Dynamic Range and Mastering

It is possible that you have heard the term ‘loudness wars’ as this has been a hot topic in the world of mastering since the mid-90s. Ever since the 1950s, audio engineers were trying to make their records louder than those of the competition.

The idea was that they would stand out more on the radio and would therefore attract more listener attention, which in turn would generate more sales. In the 1990s, with newly prevalent digital technology allowing levels to be pushed harder and harder, this process reached new extremes; by the late ‘90s, records were on average 18dB louder than they had been in 1980!

What does this have to do with dynamic range? Well, in order to make their masters as loud as possible, engineers had to compress them further and further. This lead to a drastic loss of dynamic range.

We’ve already discussed the reasons why dynamic range is important to the musicality of a master. It is the opinion of many mixing and mastering engineers that the loudness wars have had an extremely detrimental effect on the music we listen to. This has even led to movements such as Dynamic Range Day gaining traction as some have tried to fight back against the prevailing trend.

The End of the Loudness War?

The good news for those that enjoy more dynamic range in recordings, is that it is making a bit of a comeback! Interestingly, since 2009 the average loudness of music has started to decrease again, and that means that the dynamic range of masters is increasing once again. This is predominantly due to streaming becoming the dominant method of music consumption.

Services like Spotify build a ‘loudness normalisation’ function into their platforms, and this is normally switched on by default. This scans the music and adjusts playback volume to ensure that it matches from song to song. As playlist-listening has become more and more important, streaming services want to ensure that playback remains smooth and that listeners don’t have to reach for the volume control every time a new song starts.

\This all means that there isn’t really a need to master more loudly any more – songs have much less need to stand out on commercial radio, and a louder master won’t help them to stand out on streaming services.

Interestingly, studies have shown that if listeners are played two different masters of the same song at the same loudness, they tend to prefer the one with the greater dynamic range. This really is an argument for mastering to allow for more dynamic range in the streaming era.

Dynamic range compression is a vital part of the sound of most modern music genres, and it’s an indispensable tool in the mixing and mastering engineers toolbox.

If you’re working in these genres you’ll almost certainly use it on every mix and master you ever do. However, it’s worth considering that if you push things too far, you might be sacrificing some of the musicality of your work. Ensure that when you are creating your music, you do pay attention to its dynamic range and remember that louder does not always equal better.

Comments:

Login to comment on this post